Shravanabelagola

Shravanabelagola – so spelled by the Jaina authorities of this town but also known as Shravana Belgola and by other spellings is in more than one respect a most remarkable place of pilgrimage. Its giant image of Bahubali has already been featured in chapter two. Another first held by Shravanabelagola is in the field of inscriptions.

Nowhere else in India have a greater number been found in so limited an area, not to mention the long span of time covered by these rock-cut writings. About five hundred have been discovered; there would be even more but some have been erased in the course of time while others have been covered by erected temples. The oldest record dates from the sixth century, the last bears the date 1889. Most of them have been found on Chandragiri, the lower of the two historic hills (giri – hill).

Another noteworthy peculiarity is the fact that the history of Shravanabelagola knows of no wars having been waged for gaining possession of it and that very little damage was done to the local temples and sculptures by iconoclastic zealots. It was the awe radiating from the face of the huge statue of Bahubali, it is believed, that turned would-be vandals into admirers of timeless art.

A further first mention would go to Shravanabelagola if a list were to be compiled of sites which have become favourite places for men and women resolved to end their life by observing sallekhana, the Jaina rite of letting one’s old or sick body die peacefully by slowly reducing one’s intake of food and liquid.

This way of dying. which is no suicide and as a rule needs the permission of a superior monk, goes back to Mahavira and even further; it is uniquely Jaina and must not be confused with the Hindu practice of offering one’s life to a god or, as in the case of sari, to the burning of wives on the stake of their husbands.

The study and translation of the inscriptions, that began in 1889 with the publica- tion of a book by the Englishman B. Lewis Rice entitled Inscriptions of Shravanabe- lagola, yielded substantial support to the literary tradition that some time in the third century.

BC the great Jaina saint Bhadrabahu decided to leave North India with his sangha of monks and head south for fear of a forecast long famine. With him on his walk south was his close disciple Chandragupta, India’s first Maurya emperor who had his empire made over to his son Bindusara while choosing for himself the life of a naked Jaina monk.

On reaching Shravanabelagola, Bhadrabahu, sensing his approaching death, advised his monks to proceed south under a new leader appointed by him, while he would retire to a cave on the hill, now known as Chandragiri, to prepare himself for death by the rite of sallekhana attended to by Chandragupta, the emperor-turned-monk.

A pair of rock-cut feet mark the spot where Bhadrabahu is believed to have died. Chandragupta lived on for another twelve years. to e. 297 BC, before parting from his body the way his teacher had.

The memory of these two spiritual heroes, kept alive by story-tellers, resulted in Chandragiri becoming a sought-after site for ending one’s life the way they did. “This process of death,” writes S. Settar in his Guide to Sravana Belgola of 1981, “was more popular among saints and nuns during early stages (AD 800), and it gradually became popular among lay-disciples in the subsequent period.

Of an estimated 106 such deaths in this centre, (between 6th and 19th cent.), 64 are of monks, 11 of nuns, 23 of male lay-disciples, and eight of female lay-disciples.(…). Among notable lay- disciples there are three kings, about ten ministers and generals, two merchants, two local officials, and two warriors.”

Today, Chandragiri, thus sanctified in the course of centuries, offers the pilgrim ideal spots for quiet meditation whereas Shravanabelagola town has of late become a centre of many activities. Here the Jaina virtue of knowing how to give one’s life direction and purpose is at work.

A water supply system, a hospital, schools, guest-houses and the like have been built; and trees are being planted. A class of about thirty brahmacharis (celibate students of religion), attached to the matha temple, adds a touch of youthfulness to the historical centre of the town.

New- comers to Jainism should not miss being present when these dedicated students celebrate their morning and evening puja in the courtyard of the Matha Temple.

The above mentioned innova- tions not all have been named- are to a great extent the work of the present Bhattaraka of Shrava- nabelagola who early in his life received the honorary title of Karmayogi, a distinction reserved for religious leaders who, as the word karma (action) denotes, make it their duty to improve the living condition of their flock in matters of health, education and livelihood without neglecting the spiritual duties of their office.

The above mentioned innova- tions not all have been named- are to a great extent the work of the present Bhattaraka of Shrava- nabelagola who early in his life received the honorary title of Karmayogi, a distinction reserved for religious leaders who, as the word karma (action) denotes, make it their duty to improve the living condition of their flock in matters of health, education and livelihood without neglecting the spiritual duties of their office.

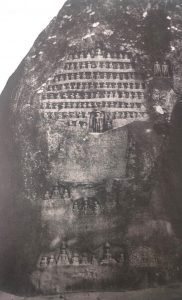

Before entering the first gate of the temple complex on top of Shravanabela- gola’s Indragiri, the pilgrim’s attention is caught by a boulder showing rock-carved monks and Jinas.