Mirpur

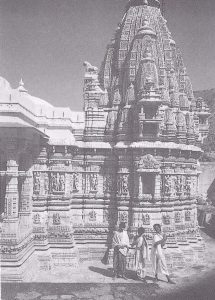

The architecturally most im- portant building near Sirohi is the main temple of a group of four at Mirpur, also known by its former names of Hamipur or Hamiryadh. A bus-ride of about fifteen kilometres to the south-west, then a half-an-hour walk along a track leading towards the Abu mountain range, and the pilgrim will find himself transported into a world where nature reigns supreme.

The architecturally most im- portant building near Sirohi is the main temple of a group of four at Mirpur, also known by its former names of Hamipur or Hamiryadh. A bus-ride of about fifteen kilometres to the south-west, then a half-an-hour walk along a track leading towards the Abu mountain range, and the pilgrim will find himself transported into a world where nature reigns supreme.

However, the “dense forest inhabited by bears, tigers and other animals of the jungle,” mentioned by Jodh Singh Mehta in his book Abu to Udaipur (Delhi, 1970: 106), has all but disappeared and is no longer a threatening danger to pilgrims on foot. Centuries ago, Mirpur was the site of a fortified town inhabited mainly by Jaina traders.

Little is known about it. Amazingly, four temples have been left standing whereas all the other buildings have vanished. The largest of the four is kept in active worship, thanks to the Seth Kalyanji temple managing body of Sirohi who also saw to it that rooms for pilgrims, a kitchen, and shelters for visiting ascetics were constructed round the remains of a garden-like courtyard.

been left standing whereas all the other buildings have vanished. The largest of the four is kept in active worship, thanks to the Seth Kalyanji temple managing body of Sirohi who also saw to it that rooms for pilgrims, a kitchen, and shelters for visiting ascetics were constructed round the remains of a garden-like courtyard.

Having taken a public bus from Sirohi and walked the last stretch on foot, we happened to reach the Mirpur temples on the day before the annual ceremony at which all the Jina images are re-anointed. Before we left later in the afternoon. we were asked to come again the next day and take part in the festivities and to taste of the food offered on such occasions.

Having taken a public bus from Sirohi and walked the last stretch on foot, we happened to reach the Mirpur temples on the day before the annual ceremony at which all the Jina images are re-anointed. Before we left later in the afternoon. we were asked to come again the next day and take part in the festivities and to taste of the food offered on such occasions.

There would be music and dancing, we were told, and Acharya Gunaratna Suri and his monks would be present too. Needless to say, we gladly accepted the invitation. Everything we could wish for would be there: a medieval temple of great beauty, a monk of high standing, a large symbol of Mount Meru wrought in silver together with all the utensils we would be able to see used in their proper way by worshippers of a religion we had come to admire. Music and dance would add a crowning touch to it.

wish for would be there: a medieval temple of great beauty, a monk of high standing, a large symbol of Mount Meru wrought in silver together with all the utensils we would be able to see used in their proper way by worshippers of a religion we had come to admire. Music and dance would add a crowning touch to it.

In short, the unexpected chance was offered to us to see and  hear what M. C. Joshi, in Vol. II of Jaina Art and Architecture, page 260, set forth in the following words (using the past tense): “The medieval Jaina shrine appears to have functioned as a centre of arts and hub of socio-cultural life intended to lead the commoner from falsehood to truth, from lower to higher truth and ultimately to the last goal of the life of a shravaka, that is moksha.”

hear what M. C. Joshi, in Vol. II of Jaina Art and Architecture, page 260, set forth in the following words (using the past tense): “The medieval Jaina shrine appears to have functioned as a centre of arts and hub of socio-cultural life intended to lead the commoner from falsehood to truth, from lower to higher truth and ultimately to the last goal of the life of a shravaka, that is moksha.”

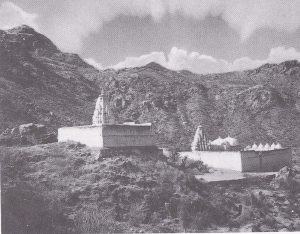

Two of Mirpur’s four Jaina temples. The right one is the best preserved.

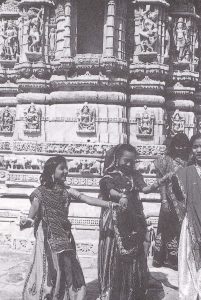

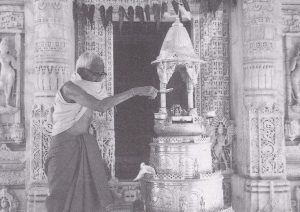

Mirpur. The pujari, a Hindu by faith, performs the ceremony during which a miniature Jina, allegorically placed on top of an image representing Mount Meru, is re-anointed. This rite is followed by reconsecrating all the other Jinas in the temple to the accompaniment of music and singing, and sometimes, as on that occasion, also dancing

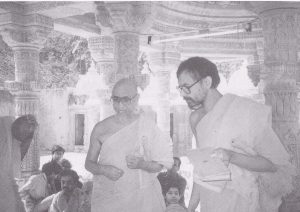

Whenever possible an acharya is invited to preside over an important ceremony; here it is Acharya Gunratna Suri (Suri is a Shvetambara honorific comparable to acharya).

Mirpur, In the book entitled Festivals, Fairs and Fasts of India (Delhi, 1996), the chapter on Jaina festivities opens with the remark: ‘Jaina festivals lack gaiety. Unbiased guests at Jaina religious celebrations will go away with a different impression, as can be seen in the above two photos. See also chapter Music and Dance in Jainism.

Ceiling mural in the smallest of the four Mir- pur shrines. It shows motifs rarely seen in Jaina temples.

CONCORD IS MERITORIOUSH

is Sacred and Gracious Majesty the King does reverence to men of all sects, whether ascetics or householders, by gifts and various forms of reverence.

His Sacred Majesty, however, cares not so much for gifts or external reverence, as that there should be a growth of the essence of the matter in all sects. The growth of the essence of the matter assumes various forms, but the root of it is restraint of speech; to wit, a man must not do reverence to his own sect, or disparage that of another, without reason. Depreciation should be for specific reasons only, because the sects of other people all deserve reverence for some reason or another.

By thus acting a man exalts his own sect, and at the same time does service to the sects of other people. By acting contrariwise a man hurts his own sect, and does disservice to the sects of other people.(…) Concord is meritorious.

King Ashoka (c. 290-32 BC), Rock Edict XII.

Speaking ill of others:

praising oneself;

concealing the good qualities of others

and proclaiming in oneself good qualities

which one does not possess:

this causes influx of bad karma.

Speaking well of others and

praising their good qualities without

drawing attention to one’s own virtues;

cultivating humility in company with others.

and to eschew pride in one’s own achievements:

this causes influx of good karma.

Mahavira

Tatvartha Sutra, VI, 25, 26