Madhuban & Sammeta Shikhara

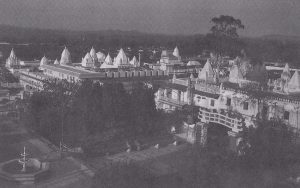

View of Madhuban at sunset

View of Madhuban at sunset

Madhuban, the easternmost Jaina “temple-city’, embedded among trees at the foot of Parashnath Hill (better known as Sammeta Shikhara or Sametshikhar), comes to life hours before sunrise.

As early as three in the morning the first pilgrims, the youngest safely tied to the back of an adult, set out on their long uphill hike by the light of torches. By the time of their return in the afternoon, they will have walked about twenty-seven kilometres; nine up, nine round the five peaks, and nine back to Madhuban.

Joining a group of pilgrims on their way to the top of this holy mountain is an unforgettable experience for the newcomer to Jainism.

The upper nine kilometres – they ought to be walked barefooted – are laid out in such a way that they guide even the inexperienced pilgrim to all the twenty and more holy spots marked by small shrines (fonks) containing footprints, but leave the highest elevation (1360 m above sea level) to the very last.

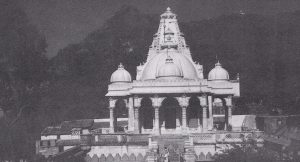

It is this last summit, visible from afar and readily recognized by its lofty temple, at which Parshvanatha is believed to have attained nirvana at the age of one hundred. That was some time in the eighth century BC.

Within the temple, in an underground cell, it is once again the Jaina symbol denoting nirvana-a pair of rock-cut footprints – onto which the pilgrims focus their rites of worship (see the footprints of Acharya Kundakunda, ill. 100). (Contowed page 216)

nirvana-a pair of rock-cut footprints – onto which the pilgrims focus their rites of worship (see the footprints of Acharya Kundakunda, ill. 100). (Contowed page 216)

The long-awaited day has come for this family group of pilgrims – the ascent of holy Sammeta Shikhara. At daybreak, the summit with its lofty temple tower will loom high in the distance.

Twenty out of the twenty-four Tirthankaras of our era are thought to have found liberation on this mountain, a location far removed from today’s centres of Jaina culture.

Going by the joyous mood in which the pilgrims set off in the small hours of the night and the happy faces with which they return, though physically exhausted, leaves no doubt that in Jainism the tradition of going on pilgrimages has lost nothing of its religious significance.

May the mentioning of this observation by a Westerner be a fitting conclusion of this  section of this book in which most of the important Jaina sacred sites are presented side by side, regardless of their affiliation to any particular sect.

section of this book in which most of the important Jaina sacred sites are presented side by side, regardless of their affiliation to any particular sect.

Sammeta Shikhara. It is the white-washed super- structure of the Lal Mandir and the Tonks dotting the easter slopes, which reflect the day’s first rays of light.

easter slopes, which reflect the day’s first rays of light.

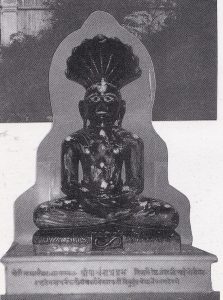

Main Jina in the Parshvanatha Lal Mandir, Due to earthquakes and other Invocs of nature, no original buildings on top of Sammeta Shikhara have survived.

Parshva Tonk, the last destination of the Sammeta Shikhara circuit that takes the pilgrim to all the hallowed spots at which twenty Tirthankaras and some of Mahavira’s disciples attained nirvana.

Parshva Tonk, the last destination of the Sammeta Shikhara circuit that takes the pilgrim to all the hallowed spots at which twenty Tirthankaras and some of Mahavira’s disciples attained nirvana.

Letting oneself be carried in a simply constructed palanquin, called doli, is a welcome means of trans- port for the weak and old and a needed source of income for the bearers, men of the indigenous people living in this area.

Moodabidri in Karnataka. Educating the young was and is of major concern to the Jainas. In this respect they had no misgivings about largely adopting the British schoolsystem.

Moodabidri in Karnataka. Educating the young was and is of major concern to the Jainas. In this respect they had no misgivings about largely adopting the British schoolsystem.

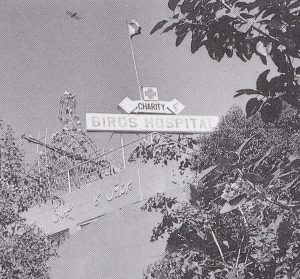

BIRDS HOSPITAL, an annex to the Digam- bara Lal Mandir in Old Delhi (see ill. 194).

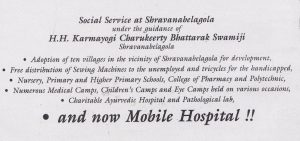

Another social service is announced by the Jaina Matha (1989). Though far outnumbered by the Hindus, the Jainas of Shravanabelagola are, guided by their leader Karmayogi Charukeerty Bhattarak Swami, the driving force in the fields of charity, education, and health service. These services are available for the benefit of all the citizens of the town.

Another social service is announced by the Jaina Matha (1989). Though far outnumbered by the Hindus, the Jainas of Shravanabelagola are, guided by their leader Karmayogi Charukeerty Bhattarak Swami, the driving force in the fields of charity, education, and health service. These services are available for the benefit of all the citizens of the town.