Symbols, Mantras And Parables In Jainism

Padukas

Stone-carved pairs of feet (padukas), mostly in high relief, are one of the oldest and most common emblems worshipped by Indians in general and Jainas in particular They usually mark the spot, apart from those seen in temples, at which an ascetic of renown is believed to have died; a corresponding inscription will often be found nearby. It would be wrong, however, to assume that padukas are to the Jainas what tombstones are to the Chinese or the Christians.

Stone-carved pairs of feet (padukas), mostly in high relief, are one of the oldest and most common emblems worshipped by Indians in general and Jainas in particular They usually mark the spot, apart from those seen in temples, at which an ascetic of renown is believed to have died; a corresponding inscription will often be found nearby. It would be wrong, however, to assume that padukas are to the Jainas what tombstones are to the Chinese or the Christians.

It is not death that they symbolize, but the soul’s conscious departure from the mortal body, an event which does not just happen as death usually does to most of us. The death of a saint is seen and understood as the culmination of life brought about through years of dedicated effort. Pairs of stone-cut feet related to a Tirthankara there are twenty of them on

Sammeta Shikhara in Bihar – symbolize final liberation usually called nirvana ot moksha. Those footprints which commemorate saints born into the present age in which, according to Jaina teaching, attainment of moksha is not possible, may he likened to sign posts or stepping-stones on the path to purification, a path that calls for at least one more incarnation as a human being.

Sammeta Shikhara in Bihar – symbolize final liberation usually called nirvana ot moksha. Those footprints which commemorate saints born into the present age in which, according to Jaina teaching, attainment of moksha is not possible, may he likened to sign posts or stepping-stones on the path to purification, a path that calls for at least one more incarnation as a human being.

This would apply, for example, to the footprints of Acharya Kundakunda near Ponnor Hill in Tamilnadu (ill. 100). It is the spirit, as expressed in the inserted prayer (opposite page), that makes the pachika such a beautiful and timeless symbol of adoration where adoration is due.

Symbolizing the Five Auspicious Events in the life of a Tirthankara

In Jaina art no attempts have been made to portray the passage of a Tirthankara’s soul from the nirvana-bhumi to the siddha-loka- from the place of death to the permanent abode of the liberated soul. This transformation, which is believed to take place within an extremely short span of time, cannot be perceived by our senses Thus it is the paduka which, in a way, symbolizes the last of the five auspicious events in the life of every Tirthankara.

In Jaina art no attempts have been made to portray the passage of a Tirthankara’s soul from the nirvana-bhumi to the siddha-loka- from the place of death to the permanent abode of the liberated soul. This transformation, which is believed to take place within an extremely short span of time, cannot be perceived by our senses Thus it is the paduka which, in a way, symbolizes the last of the five auspicious events in the life of every Tirthankara.

These five happenings are:

- (1) Incarnation in the mother’s womb;

- (2) birth and first bath on Mount Meru performed by Indra, king of the gods;

- (3) initiation into monkhood called diksher,

- (4) enlightenment and first sermon, and fifthly, as already mentioned, attainment of

- nirvana or moksha.

Accounts of these five principal events in the life of a Jina, called pancha- kalayanuka, are enumerated in old manuscripts, especially in the Kalpa Sutra by Bhadrabahu. The oldest copies of this book are written on palm-leaves, later ones (opposite), Tirumalai, Tamilnadu.

also on paper. Most of the extant copies date from about 1050 to 1750. In conse

quence of a continuous demand for this invariably illuminated book, especially popular with Shyetambaras, Jaina pictorial art became well known and gained high rating within the field of Indian miniature painting Less well known than the miniatures from the Kalpa Sutra, which one sees displayed in museums the world over and reproduced again and again in books of Indian art, are the representations of those auspicious events worked in stone and metal and found in Jaina temples all over India. The following illustration shows part of a ceiling décor in the Mahavira temple at Kumbharia in Gujarat.

![]()

Detail of ceiling depicting the first of the five auspicious moments in the life of a Tirthankara.

On the left, resting on a cot, is the sleeping mother-to-be of a Tirthankara. On her right are symbols of the approaching fourteen dreams she is about to dream. In the Kalpa Sutra, translated from Prakrit into English by Hermann Jacobi (here abridged and slightly edited), each dream opens with lines that keep ringing in one’s ears: “Then Trishala saw in her first dream a fine enormous elephant, possessing all lucky marks, who was whiter than an empty cloud, or a heap of pearls, or the ocean of milk

(2) Then she saw a tame lucky bull. of a whiter hue than that of the mass of petals of the white lotus, illumining all around by the diffusion of a glory of light…

(3) Then she saw a handsomely shaped, playful lion, jumping from the sky towards her face; a delightful and beautiful lion whiter than a heap of pearls…

(4) Then she. with the face of the full moon, saw the goddess of famous beauty, Shri, on top of Mount Himavat, reposing on a lotus in the lotus lake, anointed with the water from the strong trunks of the guardian elephants…

(5) Then she saw, coming down from the firmament, a garland charmingly interwoven with fresh Mandara flowers…

(6) And the moon: white as cow milk, or a silver cup. Such was the glorious, beauti- ful, resplendent full moon which the queen saw.

(7) Then she saw the large sun. the dispeller of darkness, the destroyer of night, who only at his rising and setting may be well viewed…

(8) Then she saw an extremely beautiful and very large flag, a sight for all people…

(9) Then she saw a full vase of costly metal, splendent with fine gold, filled with pure water, and shining with a bouquet of water lilies.

(10) Then she saw a lake, called Lotus Lake, adorned with water lilies…

(11) Then she whose face was splendid like the moon in autumn, saw the milk-ocean, equalling in beauty the breast of Lakshmi, which is white like the mass of moon-beams…

(12) Then she saw a celestial abode excelling among the best of its kind. It was hung with brilliant divine garlands, and decorated with pictures of wolves, bulls, horses, men, dolphins, birds, snakes. There the Gangharvas performed their concerts, and the din of the drums of the gods, imitating the sound of big and large rain-clouds, penetrated the whole inhabited world…

(13) Then she saw an enormous heap of jewels…

(14) And a fire. She saw a fire in vehement motion, fed with much-shining and honey- coloured ghee…-

After having seen these fine, beautiful, lovely, handsome dreams, the lotus-eyed queen awoke on her bed while the hair of her body bristled for joy.”

According to Digambara tradition a Jina’s future mother sees sixteen dreams of which the first seven correspond to the ones of the Shvetambaras. The eighth com- prises a pair of full vases with lotuses, the ninth is a pair of fish, the tenth a celestial lake, the eleventh an agitated ocean, the twelfth a golden lion-throne, the thirteenth a vimana (celestial car), the fourteenth a palace of the king of snakes (nagendra- bhavana), the fifteenth a heap of jewels, and the sixteenth a smokeless fire.

The symbols of these sixteen dreams may be seen carved on door-lintels of Digambara temples, at Khajuraho for instance, or, as it became the mode of later centuries, painted in form of murals (see ill. 196).

The dreams symbolize the incarnation of the Jina in the mother’s womb. The birth, the second auspicious event, is represented by showing the mother, either lying or sitting, with the child close to her breast. The symbol of diksha, the initiation into monkhood, has the figure of a monk sitting cross-legged and plucking out his hair with one hand, a ritual named kesh lonch (Sanskrit: kesha-luncana). For illustrations of this rite see pages 96 and 97.

The attainment of omniscience, termed kevalajnana (knowledge involving aware- ness of every existence in all its qualities and modes), the fourth of the five auspicious events and the focus around which the religion of the Jainas has become concentrated, has led to the unique and most elaborate symbol in Jainism – the samavasarana.

Fortunately, this symbol has not been reduced to a standardized module. Countless architects, temple-builders, sculptors and painters were free to use their imagination as long as they kept to a few basic elements such as having a Jina in the centre, preferably a seated one. The samavasarana, when seen as a flat painting, must not be confused with a tantric mandala. During all these centuries, Jainism, unlike Buddhism, has managed to steer clear of tantrism. Jainas

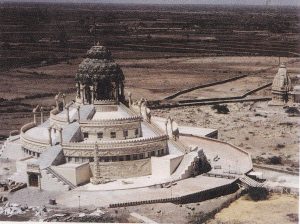

Palitana. Samavasarana- Temple, dedicated 1986.

may believe in phenomena that are close to magic, but they would never subscribe to a belief that sees in sexual union a way of enlightenment. The aim of a representation

of samavasarana, be it an old painting or a modern temple of enormous size, is to arouse in the mind of the beholder the picture of a Tirthankara’s first sermon. Whenever, according to Jaina mythology, a Tirthankara attains enlightenment and is about to deliver his message, god Indra (also called Shakra) orders the erection of a huge auditorium with flights of steps leading from the four points of the compass up to the central platform where the nude.

Tirthankara, sitting or (rarely) standing under an Ashoka tree, proclaims his message to the assembled audience consisting of monks and nuns, kings and chieftains, lay people in great numbers as well as four-legged animals, birds and even snakes, fishes and turtles. After the sermon, the auditorium vanishes the way it was built and the Jina sets out on his mission of preaching the doctrine of non-violence and the other ethical precepts.*

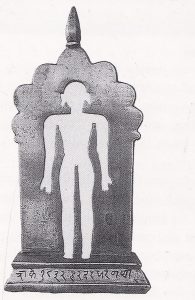

Attaining moksha, the fifth and final event in the life of a Jina, defies concrete represen- tation. Thus the rock-cut footprints may, as already suggested, be taken as a symbol of that invisible and lastly unexplainable meta- morphosis without actually representing it. The same could be said of those peculiar metal icons (left), displayed in Digambara temples, which show the stencilled outline of a human figure. They are meant to exemplify the non-material state of the soul (siddha) in the highest heaven called siddha-loku.

Image of a Siddha. 1910, North Karnataka: (Courtesy Marg Publications, Bombay)

*For a detailed account of the samavasarana see the chapter by Gopilal Amar in Jaina Art and Archi- tecture, Vol. III, 529-533. G. Amar concludes his entry with the remark: “As a matter of fact, symbol- izing even in a large structural form the vast and complex area like the samavasarana is more or less. impossible for an architect or a sculptor to achieve.” Nor for a painter to paint, it may be added. 232

Samavasarana: an assembly of beings who have come to hear a Tirthankara preach the Doctrine. 1800, Rajasthan. (Picture and text courtesy R. Kumar, co-author of The Jain Cosmology, 1981: 44/45.)

“The assembly is taking place on a huge circular mound. The area is enclosed by a wall, and cut across by four monumental staircases, which give access from the four points of the compass. At the crossing of the triumphal ways which they form, at the exact centre of the assembly and of the circular open space situated at its middle, stands the pillar from which the Tirhankara preaches the Doctrine.

The illustration shows the vast central platform, demanded by tradition. It is surrounded by three successive circular rings. On the middle ring there are wild animals, their mutual hostiliy laid aside. On the inside ring gods and goddesses, princes, layfollowers and monks are assembled.(…)

While evoking the charms of the tangible world, the artist also focusses our gaze on the prophet and attracts our attention to his unsurpassable teaching.”

The eight objects of auspiciousness: Asta-mangalas

The earliest representations of the eight objects of auspiciouness, cut into slabs of stone, have been found at Mathura among the remains of the Kushana period (64-225 AD). In the course of time they became popular objects of worship in Jaina temple rites but progressively more in the form of engraved metal platters and coloured paintings on cloth and paper rather than of stone-cut panels. Originally each of the eight symbols had its own meaning. The mirror for instance was meant for seeing one’s true self. Today they are rather looked upon as a ‘eight-in-one’ symbol. the worship of which, when offered in the right frame of mind, is believed to be a good omen. The current asta-mangala symbol is not rigidly fixed but occurs in various shapes and arrangements.

Asta-Mangala, the eight objects of auspiciousness;

Shvetambara tradition:

- (1) swastika,

- (2) sha, mark on the chest of the Jina.

- (3) nadyavarta, a diagram,

- (4) vardhamanaka, powder-flask

- (5) kufasha, full vase, the two eyes represent right knowledge and right faith,

- (6) bhadrasana, a high seat

- (7) pair of fish,

- (8) a mirror.

The Digambara tradition gives the following set of asta-mangalus:

- (1) hhrngara, a type of vessel.

- (2) katasha, the full vase

- (3) darpana, the mirror,

- (4) camara, the fly-whisk.

- (5) divaja, the banner. yana, the fan,

- (7) chatro, the parasol, and

- (8) supratistha, the auspicious seats. (After UP Shah in Jains Art and Arckilecture, 1975: 492.)

Amity and fearlessness

The emblem, showing a tigress suck- ling the calf of a cow and the cows suck fing the young of the tigress has become a favourite symbol with Digambara Jainas in this century. The story goes that some time in the eighth century, at a deserted place where Moodabidri stands today fave p. 47), a muni from Shravanbelagola saw tiger and a cow drinking from a common trough while feeding their young as described above.

The emblem, showing a tigress suck- ling the calf of a cow and the cows suck fing the young of the tigress has become a favourite symbol with Digambara Jainas in this century. The story goes that some time in the eighth century, at a deserted place where Moodabidri stands today fave p. 47), a muni from Shravanbelagola saw tiger and a cow drinking from a common trough while feeding their young as described above.

The panel pictured here seen by the present author above the gate of the Jaina Basadi at Nandani near Kolhapur (see map p.281, which was built, according to the Bhattaraka of the locality, in 935. This sculpture, though perhaps of later date, would still be one of the earliest specimens of this attractive motif

Shruta-skandha Yantra

332 (left). An interesting version of the Shruta- Skandhu Yantra (literally scripture – assem- blage-diagram), photographed in a Tamilnadu Digambara temple. The central pillar symbol- izes Sarasvati, the goddess of learning. To show that the earliest scriptures were written on leaves, the artist gave the twelve limbs the shape of palm-leaves; the letterings inscribed on them specify the titles of the twelve main texts (agamas) of the Jaina canon. Shruta- skandha yantras are usually made of brass or bronze. No two of them seem to be alike.

blage-diagram), photographed in a Tamilnadu Digambara temple. The central pillar symbol- izes Sarasvati, the goddess of learning. To show that the earliest scriptures were written on leaves, the artist gave the twelve limbs the shape of palm-leaves; the letterings inscribed on them specify the titles of the twelve main texts (agamas) of the Jaina canon. Shruta- skandha yantras are usually made of brass or bronze. No two of them seem to be alike.

Sthapanacharya

The Sthapanacharya, a compound word made up of sthapana (installation) and acharya (head monk), is peculiar to Shvetambara monks and nuns. It is a small stand of three crossed-sticks, like the letter X, on which five round pieces of sea-shell, wrapped in a cloth, are placed. Each day anew, monks and nuns, no matter of which rank like to ‘install’ the stapanacharya in front of them as a symbol of their respective spiritual teacher, regardless of whether he is temporarily absent or has already died.

The Sthapanacharya, a compound word made up of sthapana (installation) and acharya (head monk), is peculiar to Shvetambara monks and nuns. It is a small stand of three crossed-sticks, like the letter X, on which five round pieces of sea-shell, wrapped in a cloth, are placed. Each day anew, monks and nuns, no matter of which rank like to ‘install’ the stapanacharya in front of them as a symbol of their respective spiritual teacher, regardless of whether he is temporarily absent or has already died.

Westerners need not hesitate to ask a monk (or nun) they are visiting to show and explain to them the sthapanacharya or, for instance, the intricate mechanism of the fly-whisk, the most characteristic symbol of Jaina mendicants, which is, among the Shvetambara, Terapanthi and Sthanakavasi, of woolen tufts, whereas the Digambara prefer peacock feathers for theirs.

The photo shows Acharya Vijaya Vallabh Suri (1870-1954, see page 136). The sthapanacharya in front symbolized to him the spiritual presence of his guru Acharya Vijayanada Suri, the one who had been invited to participate in the first Chicago Conference of World Religions in 1893, but which he could not attend (see page 250).

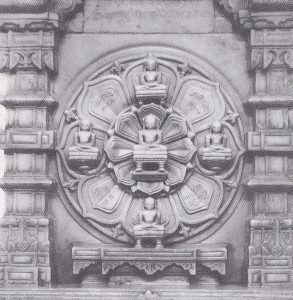

Siddha-chakra

Ajitatho Temple, Tarangs Siddha-chakra (saint-wheel) or -padi (nimine). Marble relief embosomed in the outer wall of the eastem one of the two outbuildings situated within the temple compound.

Ajitatho Temple, Tarangs Siddha-chakra (saint-wheel) or -padi (nimine). Marble relief embosomed in the outer wall of the eastem one of the two outbuildings situated within the temple compound.

At first, how carly is not known, the siddho-chatra of both the Digambaras and Shvetambaras was confined to a lotus of four petals, with a representation of the Arhat in the centre. Paterned in this way it may also he called pancha-parmet, with which the five dignitaries are meant the Arhuts, Siddha Acharya, Ups and Suar.

The eight-petalled nido-chakra (ill. 334 above and 336, opposite), either cut in stone, cast in metal or paimed on cloth or paper, appeared the eleventh century, but by then cach of the two big sects employed a different pattern the Shvetan bara named theirs navo-pads the Digambara na-devota However, the term ho-chan is med as the common term for all the different forms of the saint-wheel.

Thus the Shvetanbaras call the festival, held around the end of winter, at which they offer worship to the symbols representing the Five Dignitaries and the Four Essentials, Siddha-chakra Mahapaja On that occasion colourful sds-chakra madalas are designed and composed in the temples out of rice and different grains, seeds, and blue and black pulse.

For the Shvetamburas the four essential’ are Right Knowledge Right Faith, Right Conduct and Right Penance. For the Digambaras they are the fina image, the Temple enshrining the image, the Wheel of Law, and the Scriptures Figure of eight-petalled Sula-chakra.

Shvetamhara

- 1- Arbat

- 2-Siddus

- 3-Acharya

- 4- Cipallysque

- 5-Sadni

- 6-Jana (right knowledge

- 7-Durhama (right faith) 8-Churana (right conduct)

- 9-Tapas (right penance)

Digambark

- 1 to 5 as above 6-Chutvo (the Fina image)

- 7-Chantralaya (temple enstarining the outs

- 8-Dharmachakra (wheel of law)

- 9-Sarar (represented by a book stand)

* Referred to in form of short mantras on petals 6 to 9

Matha Temple, Shravanabelagola. Digambara Nava-devata metal image. Height 44 cm. Cast in Tamilnadu and, according to an inscription on the reverse. presented to the Matha by a layman named Perumal in 1858.

Tha Jaina Faith And Universe

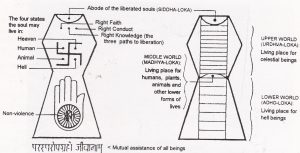

Prior to the 2500th anniversary of Maha vira’s nirvana in 1974/75, the leaders of the various laina sects found themselves under the necessity of devising a common symbol for the Jaina religion: all other religions seemed to have one.

Prior to the 2500th anniversary of Maha vira’s nirvana in 1974/75, the leaders of the various laina sects found themselves under the necessity of devising a common symbol for the Jaina religion: all other religions seemed to have one.

They agreed on the diagram shown above. A new composition of old elements like the svastika and the wheel of law. New is the fettering in the centre of the wheel meaning Ahimsa The phrase in Devanagari, script below the diagram denotes, “All life is bound to gether by mutual support and interdependence.”

The eight black fields’ in the third layer of the Brakmaloka. Gouache on paper, eighteenth century (Courtesy R Kumar The Jain Cosmology)

The discovery of black holes by our astrono mers is of rather recent date. Interestingly, Jaina cosmology speaks of eight black fields, which are not, however, described as holes but as thin layers of watery and greatly swollen vegetable fragments (of waste so to speak) that arise from an ocean of the middle world that part of the verse in which we live right op to the dizzy hights of the brakenalk the fifth heaven of the gods That astronomical event is stylistically depicted it is painting from Rajasthan.

337 b. Diagram showing in a stylized form the Jaina universe based on descriptions in old manu- scripts and paintings which emerged in Jaina art from around the sixteenth century onwards. In many of these illustrations which have come down to us, the universe is shown in the shape of a human being (purusha), who can be either female or male. Descriptive details of the Jaina cosmos, here and there touched upon in the present book. are found in most English publications on Jainsi.

Mural painting covering the rear wall of the Assembly Hall in the Terapanthi Adhyatma Sadhana Kendra, at Mehrauli, New Delhi. The picture on the right illustrates how the mental and moral level of a person can be judged by the colour (leshya) of his soul. The popular parable of the ‘Man in the Well’ is the motive of the picture on the left. Paintings with these contents are found in many Jaina temples.

The tree with the six persons illustrates the six leshyas of Jaina philosophy. Leshya (tint) is that by which the soul is tinted with merit and demerit. It is of six kinds and colours, three being meritorious and three sinful. Meritorious leshyas are of orange-red, lotus-pink and white colours, while sinful leshayas are of black, indigo and grey colours. The former lead respectively to birth as man and to final emancipation, while the latter lead respectively to hell and to birth as plant or animal.

The picture illustrates the acts of persons affected with the different tints. With the desire of eating mangoes a person under the influence of the black leshya cuts the trunk of the tree; another affected with the indigo chops off big boughs; a third influenced by the grey cuts off small branches; a fourth affected with the orange-red breaks the twigs, a fifth under the influence of the lotus-pink merely plucks mangoes; and a sixth affected with the white picks up only fallen fruit. (After Saryu Doshi in Homage to Shravana Belgola, 1981: 35.)

There exist several versions of the popular parable of the Man in the Well’. A concise account would run as follows: A merchant lost in the jungle fled from the attack of a mad elephant and now clings to the branch of a tree he has grabbed just in time, Casting his eyes downwards he looks into a black water-hole full of snake-like monsters. Looking skywards he sees a hive alive with bees. Whenever the elephant shakes the tree with his mighty trunk, honey drops down from the hive right onto his tongue.

There exist several versions of the popular parable of the Man in the Well’. A concise account would run as follows: A merchant lost in the jungle fled from the attack of a mad elephant and now clings to the branch of a tree he has grabbed just in time, Casting his eyes downwards he looks into a black water-hole full of snake-like monsters. Looking skywards he sees a hive alive with bees. Whenever the elephant shakes the tree with his mighty trunk, honey drops down from the hive right onto his tongue.

A deva (god), passing by in his vimana, catches sight of the man in distress and calls out to him that he will come to his rescue. The man shouts back that he need not hurry for he would like to relish the taste of the honey somewhat longer.

At the same time, he takes no notice of the two rodents, one white the other black (symbolizing day and night), which keep gnawing their way through the stem of the branch he is on. The god, taking his time, sees the man slipping off the breaking bough and falling into the hole where he is seized by the hungry monsters.

This in a nutshell is the way many a human lives his life. Though being aware of the threatening danger and perceiving the message of a potential saviour, his desire for a few more pleasures of the senses prevents him from taking advantage of the offered help.

Offerings

Whilst invoking the name of the respective Jina during temple worship,

the following eight substances are offered:

- (1) Water,

- (2) uncooked rice,

- (3) flowers,

- (4) sandalwood paste mixed with saffron,

- (5) camphor,

- (6) incense,

- (7) sweets and

- (8) fruits.

The presentation of flowers is practised by some sects but contested by others. Uncooked rice, the primary substance, is chosen for its whiteness and for having been born only once. At no stage in the long history of Jainism have animals been used as offerings.

The breaking of a coconut upon a stone positioned for this purpose in front of the entrance to a temple (see ill. 318) is another rite with a symbolic content. The coarsely knit fibres of the coconut are thought to represent jealousy, greed, lust, selfishness and the like.

This coarse layer, corresponding to the layers of karma encompassing one’s soul, needs to be broken and removed before one reaches the sweet, nectar-like liquid, which. pure throughout and untouched by any hand, symbolizes that purity of soul one should strive for. The three eyes of the nut, which no other fruit has, stand for Right Faith, Right Knowledge, and Right Conduct: the Three Jaina Jewel

Chart of Meditation on Namo Arihantanam, after the late Acharya Sushil Kumar (see page 92 in his Song of the Soul).

The Namokar Mantra-the Song of the Sout

The late Sthanakavasi Acharya Sushil Kumar (1926-1994), the first Jaina ascetic who dared to trespass the rule that bans the use of mechanical transport for mendi cants, was a great master of meditation and the science of sound. As a child, though born into a Hindu Brahmin family, he had discovered the power of the Namokar Mantra that was taught to him by a Jaina muni.

At the age of fifteen he himself became a Shvetambara Sthanakavasi monk. In his small book Song of the Soul-An Introduction to the Namokar Mantra, he writes, “A valuable question to ask yourself is-what is your goal? What do you want to become in this life? To this question, 1 must answer that the Namokar Mantra my goal and my life. It is my life and destiny.

Through it I can serve and guide along the path of non-violence.(-) So when I came to America (that was in 1975, the editor), I decided to teach the science of sound vibration according to the Arihant tradition. The ancient teachings of the Arihantas are very powerful, very clear and true, and the Namokar Mantra is the essence of that knowledge. This small book will simply introduce you to the mantra’s power.”

Jainas of all denominations chant and sing the Namokar Mantra in Prakrit. the language in which it was composed at an unknown date many centuries ago. It consists of just five lines of text and two appended lines.

They read as follows:

- Namo Arihantanam_ (I bow to the Arihantas, the Jinas, the perfected human beings)

- Namo Siddhanam_ (I bow to the Siddhas, the liberated bodiless souls).

- Namo Airiyanam_(I bow to the Acharyas, the leaders of the Jaina congregations).

- Namo Uvajjhayanam_(I bow to the Upadhayayas, the spiritual teachers).

- Namo Loe Savva Sahunam _(1 bow to all the Sadhus (ascetics) in the world)

Eso pancha namokaro savva pavapanasno

mangalanamcha savvesim padhamam havai mangalam. (This five-fold obeisance mantra destroys all sins and obstacles, and of all auspicious repetitions, it is the first and foremost.)

“In the Namokar Mantra,” Acharya Sushil Kumar continues to say, “we pay homage to the five divine personalities, but they are not separate from us. They are actually symbolic of noble qualities, or states of consciousness, which we are striving to attain. They do not represent different paths to the goal of liberation but rather, various states in the evolution of the soul. If we are spiritual practitioners, then in essence we are Sadhus, and we can progress to the ultimate states of Arihant and Siddha, and attain liberation.”

Published in 1987 by Siddhachalam Publishers, 65 Mad Pond Road Blairstown, New Jersey 07825, USA. This also the address of the main Ashram founded by the late Acharya Sushil Kumar in the USA

**Page 28 in The Namokar Manirathe Song of the Soul

Indian people are essentially a musical people. They use masc

for almost every function in life; whether it is a religious ceremony

or a social function or an agricultural pursuit they won’t hesitate to

use music to lighten their hearts and make their burden less heavy

R. Srinivasan Facets of Indian Culture, 3rd ed. 1980: 48