Halebid

The capital of the Hoysala kings who ruled for nearly three centuries, from 1047 to 1343, was, for most of the time, what today is the vilage of Halebid(u) – hale – old, bidu- capital.

There is evidence to presume that the Hoysala dynasty came to power with the help of a Jaina ascetic by the name of Shantideva. Bittiga, the considered greatest king of the Hoysalas, began his reign, that lasted from 1106 to 1141, as a Jaina.

Later, having come under the sway of the erudite Hindu teacher Ramanuja, he converted to the Vishnuite branch of Hinduism and changed his name to Vishnu- vardhana. None the less, his queen, Shantidevi, remained an active follower of the Jaina religion.

Her steadfastness, one may assume, will have facilitated the con- tinuous building of Jaina temples at Halebid and other places in the Hoysala kingdom which included present-day Karnataka. Nowadays, the term ‘Hoysala’ stands for a distinctively South Indian style of temple architecture and sculptural art that devel- oped under the rulers of Halebid. A characteristic component of Hoysala art is the use of black schist, a stone suitable for fine carving.

About four hundred metres south of the enclosure with the famous Hoysala Hindu temple of Halebid and the museum, there stand, arranged in line and within a well-kept compound, three Jaina temples. All of which face north, making them difficult to photograph, specially during the winter months, the best time to visit them.

About four hundred metres south of the enclosure with the famous Hoysala Hindu temple of Halebid and the museum, there stand, arranged in line and within a well-kept compound, three Jaina temples. All of which face north, making them difficult to photograph, specially during the winter months, the best time to visit them.

The temple at the westernmost end is dedicated to Parshvanatha, the next in line, which has no pillared hall in front, to Adinatha and the third one to Shantinatha. All three are in active worship for the benefit of the pilgrims. The other Jaina temples of Halebid are in a lesser state of preservation.

The interior of the three temples depicted in illustration 61 could be interpreted as a grandiose manifestation of perseverance. The massive pillars, placed so close to each other, give the impression that there is more for them to support than the roof alone.

Are they meant to remind us of the accumulated weight of the many layers of karma that presses down on us? At the same time, they – the polished black pillars – seem to convey the message that this is no place to lament the passing of time. Timelessness seems to be their message.

Thus, logically, the builders of these temples contrasted the inertia of the perfectly balanced pillars not by seated Tirthankaras – that would have been too much of the same intention – but by a typically Jaina equivalence of ‘time-does-not-matter, that is, the Jina in the ‘abandonment of the body’ (kayotsarga) posture. It is the three standing Thirtankaras, one in each temple and equal in height to the weighty pillars, that prevent the notion of heaviness from becoming oppressive.

Time is ever-lasting and of little concern. To reach this blessed stage of awareness while still treading the roads and by-ways of this world is a major aim of the Jaina pilgrim who comes to this and many a similar place of worship.

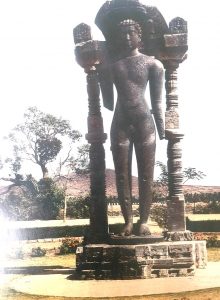

To symbolize the successful shedding of heaviness, the picture of a  Hoysala Jina in kayotsarga pose, initially worshipped in a Halebidu temple and now displayed outside the local museum, has been chosen for the cover of this book (see following page).

Hoysala Jina in kayotsarga pose, initially worshipped in a Halebidu temple and now displayed outside the local museum, has been chosen for the cover of this book (see following page).

Halebid. Museum compound. Statue of a Jina in kayotsarga pose.

Hoysala style. Black stone.