The Jaina Art Of Gwalior And Deogarh

Klaus Bruhn

Three seasons in a hospitable Indian village and the support of a co-operative Jaina community are remembered to this day, and I am grateful to KURT TITZE for an oppor tunity to return to a subject which I studied almost forty years ago as a young scholar.

However, the present paper is not just an excursion into the past. No doubt the Jaina images and Jaina temples of Deogarh, as I saw them in the fifties, are still before my eyes, perhaps also an indication of the fact that in those days young scholars had more time at their disposal than today: rather than hurrying from place to place they could absorb the impressions of a single place or a limited area.

But in spite of vivid memories of past days, I have this time not only repeated results of earlier research in a condensed form, but also tried to show that Deogarh must be viewed in a wider regional context. This implies the inclusion of the Jaina sculptures of Gwalior, and it also implies occasional references to the whole of Central India-the art province to which Gwalior and Deogarh belong. The inclusion of Gwalior was possible thanks to the generosity of GÜNTER HEIL (Berlin) who provided the photo negatives for our illustrations.

Jaina art begins at Mathura shortly before and under the Kushana dynasty at c. 100-250. If we make some allowance for a period of limited activity, we can say that a new phase started under the imperial Gupta dynasty of Northern and Central India (320 to c. 500). The centre of Jaina art was still Mathura, but in the subsequent periods the activities of the Jainas spread to other places as well.

In spite of continuing artistic activities, Jaina art in Central India regained its former importance only at a somewhat later date with Gwalior and Deogarh becoming centres of Jaina art (Gwalior: 700-800, Deogarh: 850-1150). The two places re- present a new phase which is, on the whole, typical of Central India and which can be called a regional style.

Before considering the sculptural art of Gwalior and Deogarh, we will say a few words about the general topographical and historical situation. Throughout the article, the reader will find references to the chronology of the monuments which are discussed or mentioned. Even a casual study of art objects cannot do without chronology.

The treeless Fort-rock of GWALIOR rises abruptly from the plain on all sides. It can boast of a number of exquisite Jaina sculptures. Some are rock-cut and facing narrow ledges in the vertical walls of the solid rock. Others are free standing (not rock-cut) and have survived on the plateau; they are now mostly kept in the newly built Archaeological Museum. Our chronological frame for the Jaina sculptures, which must have been executed by more than one generation of artists, is 700-800.

In spite of the iconoclasm of the Islamic invaders, the early Jaina sculptures of Gwalior have survived in fairly good condition so that their former splendour is not lost. The relief’s reproduced by us are cut into the cliff-wall below the Ek-khamba Tal (tal-tank) on the western side of the Fort-rock (south-western group), but there are early Jaina sculptures at other points as well. Naturally, Gwalior is above all a Hindu site.

Two Hindu temples of the early period are still extant, the famous Teli-ka- Mandir (750-800) on the plateau and the small rock-hewn Caturbhuja Temple (876) a short way up on the left of the approach-road leading to the plateau.

A medium-sized Jaina temple, dated 1108, has survived in dilapidated condition. However, there was a revival of Jaina art at a much later date, viz. in the 15th century under the predecessors of Man Singh Tomar (1486-1516).

Several groups of Jina figures have been excavated in the steep cliff immediately below the walls of the fortress. “The rock sculptures of Gwalior are unsurpassed in North India for their large number and colossal size but from the artistic view point they are degenerate and stereotyped.” Well-known is the Urvahi group (“The western side of the hill is broken by the deep gash of the Urvahi ravine”). The largest Jina image of this group is a standing colossus measuring 57 feet (17.4 m) in height.

However, the south-eastern group, half a mile in length and situated under the Gangola Tal is even more important than the Urvahi group. In 1527, the Urvahi Jinas were mutilated by the Mughal emperor Babar, a fact which he records in his memoirs. Babar wrested Gwalior gradually from the governor of the former Delhi Sultan who had taken possession of the Fort in the days of Man Singh’s son.

The rigorous iconoclasm of the Muslim invaders is well-known, but this is not to say that there was permanent hostility between Muhammedans on the one hand and Hindus and Jainas on the other. Often the contacts between the communities were so close that the orthodox members on both sides feared that their respective religions might lose their influence on the believers. Still, to this day the damage once caused by the invading armies can be seen in the whole of Northern India.

Hindu art flourished at Gwalior in all periods. In 1093, Hindu architects completed the two Sas Bahu temples, both lavished with decoration, on the plateau of the Fort-rock of Gwalior, Much later. Gwalior came under the rule of the Tomara dynasty with Man Singh Tomar as the most prominent figure. This king built the magnificent Man Mandir and the Gujari Mahal, two palaces which are amongst the earliest specimens of Rajput architecture.

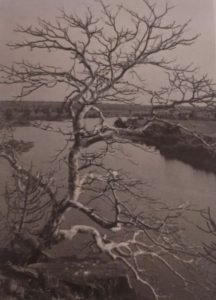

DEOGARH, situated further south, is a small village which can be reached by a metal-road from Lalitpur (see map, p.100). The village is situated in the low-lying lands (Valley”) at the foot of the Fort-hill on the right bank of the River Betwa. The ancient monuments are found partly on the Hill, within the circumference of the old Fort-wall, and partly in the Valley and near the village.

Generally, the Hill does not stand out sharply from the surrounding area, but on its southern side it is cut by the River Betwa, a tributary to the Yamuna and the Vetravati of Sanskrit literature. Flowing for the most part in a rocky bed, the Betwa forms a series of deep pools and picturesque cataracts.

The narrow gorge where it forces its way through the Vindhyan hills and the magnificent sweep it makes below the steep sandstone cliff which is surmounted by the Fort of Deogarh is a scene of striking beauty” Deogarh is known both for the Gupta Temple (500-550) near the village and for the group of Jaina temples in the eastern part of the Fort (850-1150).

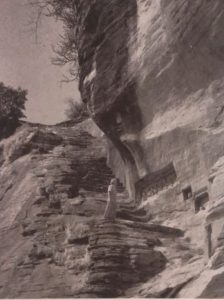

The Fort is over- grown with jungle which had not been completely removed from the Jaina mono- ments before the visit of DR.SAHMI of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1917/1918. There are also various other monuments in the Deogarh area, most promi- nent being the dilapidated Varaha Temple on the Fort (700-800) and the sculptures (mother goddesses and other Hindu idols) cut into the cliff-wall (ill. 161) along the three ghatis or flights of steps leading from the Fort down to the River Betwa (550- 700).

The Gupta Temple with its rich sculptural decoration is one of the great Hindu monuments of the Gupta period, and the sculptures (mostly images) of the Jaina compound (850-1150) are important on account of their stylistic and iconographic variety. The sheer number of images is impressive; not all of them, but more than four hundred can be labelled as ‘deserving description” (see also References III). The material of the Deogarh monuments is sandstone, often of a warm brick-red colour.

The name ‘Deogarh is of little consequence. There are many places named ‘Deogarh’ (‘fort of the gods’). Fortifications which encompass temples are certainly not rare, and ‘Deogarh may thus have become a popular designation for villages in the vicinity of temples within fort-walls.

Furthermore, the present village is a settlement without history. In 1811, the Fort was wrested by a Colonel Baptiste from the Bundela Rajputs as we read in the Imperial Gazetteer of 1908. To date, nobody has tried to reconstruct the local history from the edited inscriptions recovered from the Hill or the Valley, and we do not know whether it will ever be possible to transform the scattered epigraphical evidence into a coherent account of the site.

No doubt, we can date most of the remains on stylistic and palaeographical grounds, but these datings do not solve all the problems connected with the locality. We know the history of the dynasties ruling over this area, but we do not know what role the Fort-hill and the surrounding territory played in the wider political develop ments. We also do not know how far the ruling dynasties encouraged building activities in a particular area. The construction of the Jaina temples of Deogarh was at any rate an internal affair of the Jaina community as a merchant community

The richness of the extant material and the clouded history of the locality call for an intensified evaluation of the available data and for the collection of new data. The debris of Hindu and Jaina monuments is promising material for the art historian, those Hindu and Jaina inscriptions which are still unpublished (some important and

some not) can be properly edited, and trial trenches can be made, both on the hill and in the adjacent Valley. Such trenches might bring to light foundations of lost Hindu or Jaina temples to which a good number of the exposed sculptural fragments must be traced back. Further fragments below or even on the surface could be secured by adequate exploration of promising localities.

Whether studies on these lines will produce a consolidated historical account we know not, but it is certain that they will give us a more complete and hence a more satisfactory idea of the site than we have today. “Deogarh is certainly more than the sum of its published monuments.

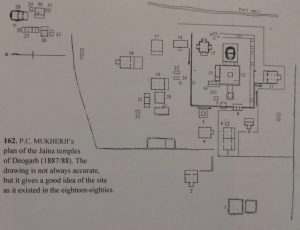

The Jaina temples (thirty-one according to DRSAHNI’S counting) differ in character, size, and age (kee ill. 158, 159, and 162): some have considerable architectural merit, while others are basically shelters for the accommodation of images. The temples and images belong to two distinct periods, which we call “early-medieval (850-950) and medieval (950-1150) respectively.

The buildings and the images have suffered considerably under the devastation of the Islamic iconoclasts as well as under the effects of vegetation and temporary neglect. but there must also have been intervening schemes of reconstruction (firnoddhar as the Jainas say).

All the details are unknown. Moreover, the building of the Fort (in 1097, or earlier, under the name of Kirtigiridurga) must have been an event of considerable importance that affected the life of the Jaina community and the man- agement of the temples to a large extent. The responsible Jaina community lived perhaps at some distance from the group of temples, as is the case today. but Hindu settlements must have been in the vicinity.

The Imperial Gazetteer records that Jains occasionally still worship there. After 1930, when the Jaina temples were placed under the jurisdiction of the local Jaina committee, modern restoration work started. In the beginning, the emphasis was on preservation, circumspect reconstruction, and general maintenance of the temple group.

There were hardly any changes made in the archaeological substance, although the construction of the Great Wall implied that the sculptures were set in mortar. This wall was built in those days in order to accommodate the majority of the vast number of sculptures lying in the Jaina compound in the open air. When all the absolutely necessary work had been completed, new activities started (in the sixties), and the idea of preservation ceased to be the sole consideration.

The place had to be made attractive for pilgrims and other visitors alike. Besides, protective measurements became necessary. In 1959, art robbers had looted the temples, cutting off and pocketing the heads of many Jina figures. We are told that the miscreants were caught, but actually no accurate information is available about the culprits and the whereabouts of the booty.

Subsequently the Temple Committee of the Jainas have taken various steps to ensure a better protection of the sculptures. They have also changed the general character of the site in so far as the Jaina temples are no longer lonely monuments in the jungle but rather elements of a comfortable park-like area which betrays a philosophy of improvement.

However, in some cases, sculptures and minor structures have been treated in a way which makes the study of old photo- graphs necessary for the art-historian. This would speak for future co-operation of the responsible bodies with experts whenever extensive work is undertaken in connec- tion with religious sites. Likewise, the management guidelines for the UNESCO’s World Cultural Heritage Sites might be taken into consideration.

The art province designated by us as CENTRAL INDIA is not well-defined, and yet some regional term cannot be dispensed with in a discussion of Deogarh and Gwalior. Ignoring the question of the southward extension and concentrating on Jaina remains, we will say that Central India includes Madhya Pradesh (with Gwalior) as well as adjacent parts of Bihar, of Uttar Pradesh (with Deogarh), and of Rajasthan.

Outside Central India, the style of the Jaina monuments clearly changes. In Central India Jaina monuments outside Gwalior and Deogarh are rare in 550-950. Images have come to light, but not in great number, and noteworthy instances of Jaina architecture are hardly to be found.

The only clear exception is the great Maladevi Temple near the village of Gyaraspur “perched picturesquely against a ledge of a hill supported on a high masonry platform” and built in 850-900. Gyaras- pur belongs to Madhya Pradesh and is situated south of Bina Junction. About forty kilometres south-west of Gyaraspur is another important site, Bhilsa (now called Vidisha) with the nearby Udayagiri Hill.

This locality was chiefly a Hindu centre but it has also produced a number of Jaina sculptures which date from the Gupta period to medieval times (400-1150). It is unnecessary to add that Mathura in the north has likewise yielded important Jaina sculptures in the period under review.

It is possible that the Jaina art of Deogarh was influenced by the Jaina art of Gwalior, but conclusive evidence for direct influence is lacking. Be that as it may, there are points of contact between Gwalior and Deogarh. A systematic survey of the Hindu and Jaina sculptures of Central India in the somewhat neglected period from 550 to 950 is at any rate a clear desideratum.

In the medieval period (950-1150), the realm of Jaina art expands, as a sequel of the expansion of the realm of Hindu art. There was an almost explosive development of Hindu and Jaina art which spread a carpet of fairly homogeneous monuments over the whole of Central India. Dozens of place-names could be mentioned for Jaina art, but we refer in this context only to Khajuraho.

At Khajuraho (Madhya Pradesh) we find a group of medieval Jaina temples as well as exquisite medieval Jina images. A survey of Jaina art after 1150-our lower boundary for medieval art – will focus attention on isolated developments such as the uncomely (and insufficiently explored) later rock-cut sculptures at Gwalior which belong to the 15th century, Apart from this specific development, the Jaina art of Central India does not extend beyond the medieval period.

Various Central-Indian Jain temples, often built in groups, form a chapter in the history of Jainism rather than a chapter in the history of Jaina art. The dominant ant region in post-medieval times-religious art, Jaina and non-Jaina – was WESTERN INDIA rather than Central India, but that is not part of the present report

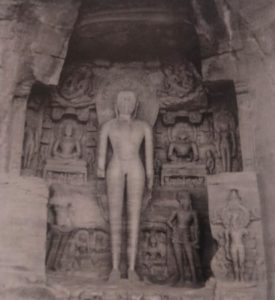

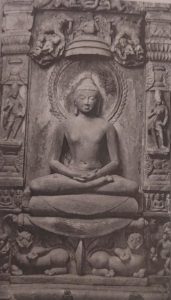

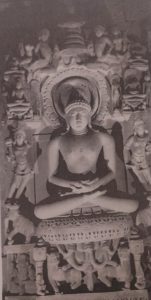

Jina composition with sub- sidiary Jina figures, Gwalior Fort (Pos courtesy CANTER HERE)

Jina composition with sub- sidiary Jina figures, Gwalior Fort (Pos courtesy CANTER HERE)

The descriptions which follow demonstrate the Jaina art of Gwalior and Deogarh and tell us at the same time what a Jina looks like or may look like. Let us mention in advance that the Jinas are normally shown stark naked.

Jinas wearing a dhoti are only found in the Shvetambara art of Gujarat and South Rajasthan. The naked Jina is standard, and only the open split, some time in the first half of the first millennium AD, into Digambaras and Shvetambaras introduced the new element. ‘Digambara’ monks were then invariably naked while ‘Shvetambara’ monks always wore a dhoti, and this difference prompted the Shvetambaras to project their monastic dress on the Jina figures.

Furthermore, Jinas are only shown in two postures: standing in meditation or seated in meditation, and hence they are always shown motionless. Jainism stands for external inactivity as the best protection against harmful actions, and this philosophy is possibly at the root of the choice of only two postures which both indicate meditation and deny external activity.

Jaina images at Gwalior

The extant Jaina images of Gwalior display a remarkable thematic variety. We find Jina images and panels, two Jina compositions, one representation of Bahubali, the meditating saint, who is well-known on account of the huge statue at Shravana Belgola, and two compositions which show the resting queen (‘mother of the Jina) and Kubera-and-Ambika respectively. The Gwalior images are mostly rock-cut (cut into the cliff), and we will here concentrate on this part of the material.

Our ilt 149 (above) and 150 (opposite) show one of two big Jina compositions which take the

form of niches in the steep rock. A tall Jina in the centre is flanked at waist-height by four

additional finas, two on either side. The central Jina motif is enriched by the addition of further

Jin Rures (1-4) and by the representation of numerous miracle motifs. Most of these miracle mo- nts are contained in a list of eight as known from Jaina literature:

| (1) An Ashok tree | (2) shower of flowers |

| (3) heavenly music | (4) two Oy-whisks |

| (5) a throne | (6) a halo |

| (7) heavenly drum(s) | (8) parasol(s) |

The expression miracle motif refers to emblems of royalty which surround the Jina in a singular manner. The motifs monly belong to the common stock of ancient Indian iconography – Hindu. Bad- hist, Jaina-which developed during and after the Kushatta period.

They surround the figures of gods and saints and are arranged according to the laws of symmetry. When the motifs had already come to stay in art, they found their way also into the literary tradition, where they are described in great detail (see below) It is important to know that the number of miracle motifs used in the representation of the Jinas differs from period to period and from region to region

We select for our analysis the central Jina and the seated Jinas to his left and to his right. The Highly stylised Ashoka tree is visible above the central Jina (foliage on both sides) and also above the sented in to the right. The shower of flowers is probably represented by the divine figures hovering above the line and flanking the triple parasol roof (see below):

We notice in the case of the central Jins two divine comples, and in the case of the two lateral seated Jinas two single figures (male figures). The divine couples occupy a prominent place in the composition. The garlands, mainly in the hands of the male figures, link the motif with the shower of flowers as listed in literature. As usual, the heavenly is not represented, whereas the fly-whisks, the and the halo are all included Into the iconographic programme.

However, we do not see detached fly-whisks hovering in the air, but ny-whisks in the hands of human figures. The throne (shown along with the two seated Jinas) takes the form of a lion-throne, i.e. a throne resting on two supports in the form of lions. Between the two lions. a dharmachakra (wheel of the law”) is represented. It is seen from the edge, and it is adorned with

resting on two supports in the form of lions. Between the two lions. a dharmachakra (wheel of the law”) is represented. It is seen from the edge, and it is adorned with

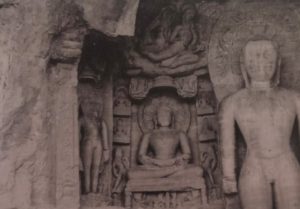

Detail of the niche composition of ill.

The so-called ‘mother of the Jina. Gwalior Fort (Courtesy GUNTER HEIL)

The so-called ‘mother of the Jina. Gwalior Fort (Courtesy GUNTER HEIL)

ribbons issuing on both sides from the hub. In Central and Eastern India, the lion-throne appears in the medieval period even below standing Jinas. The halo is omnipresent in Indian iconography and requires no comment.

Two drams are visible above the halo in the case of the central Jina, and in the top left and top right corners of the panels with the two seated Jinas. The last ‘miracle’ is the parasol. It takes in the case of the Jina normally the form of three superimposed parasol roofs.

In literature, the miracle motifs as just described are connected with a specific event in the biogra- phy of the Jinas. Whenever a Jina was about to deliver a sermon, the gods built for him a circular ditorium, or sumuarana, where he was to occupy a raised seat under an Ashoka tree in the centre of the structure. Here the saint was not only honoured by an impressive arena, which was occupied by his fisteners, but also by the said emblems.

It must be added that the samavasarana is based on the concept of a tree sanctuary (provided with emblems of royalty) which survives in Jina iconography in unequivocal form in the tree above the Jina. Needless to add that the Jina in the samavasarana is always seated, while art shows the Jina both in seated and standing postures.

The connection between Jina image and samavasarana concept is obvious, but it cannot be called very close. Not all motifs follow the miracle type. This applies, for example, to the additional Jinas (medium size or small size), which are shown quite often and which are very prominent in the case of our composition.

The subsidiary Jinas of the composition include a standing Parshva (fourth subsidiary Jina from left), and there is a similar standing Parshva at the entrance to the rock-cut niche (right side only). Parshva images differ images from of the other twenty-three Jinas basically on account of the cobra motif.

The hood of a cobra form a hood-circle’ with seven or five hoods behind the head of the Jina, and the superimposed coils of the animal appear to the left and to the right of his body. The legend tells us that the Jina Parshva was once attacked by a hostile demon who hurled stones from above at the Jina.

At that critical moment, a benevolent snake-god came to Parshva’s rescue and spread his.

Kubera and Ambika as Jaina divinities; two miniature Jinas appear in the crowns of the trees, Gwalior Fort.

Kubera and Ambika as Jaina divinities; two miniature Jinas appear in the crowns of the trees, Gwalior Fort.

hoods as a protective shield over the meditating saint. This is the Jaina legend (concept and legend exist also in Buddhist art and literature), but actually Parshva is a form of the Jina, which reflects the influence of ancient Indian snake worship, a popular substratum whose influence is seen in Hindu. Buddhist, and Jaina iconography. A divine snake was mostly shown as a human being combined with a multi-headed snake, and the snake worshipper could thus recognize in the Jina Parshva the snake-god of his fathers and forefathers.

Out of the six Jinas we can identify only three, one Rishabha (second subsidiary Jina from left) and two Parshvas (see above). Rishabha is recognized by his peculiar hair style, which again has a corol- lary in legend.

Three Jinas, including the one in the centre, remain unidentified. The cognizances which enable us to identify all twenty-four Jinas are important in principle but only comparatively rarely shown in art. The Rishabha figure presents along with four minor Jinas a pentad within the pen- tad. In Jaina dogmatics, all twenty-four Jinas have the same religious rank, and differences in the scale as found on most multiple compositions are merely an artistic device. To the left and to the right of the central Jina we notice two panels with Jaina deities at the bottom level.

The panel to the left shows an unnamed divine group (“tutelary couple’), and the panel to the right a goddess (Jaina The motifs as such are very common in Jaina art: see ill.152 (Ambika) and ill.157 (tutelary couple and Ambika). However, the way in which they are included into our composition is unconventional

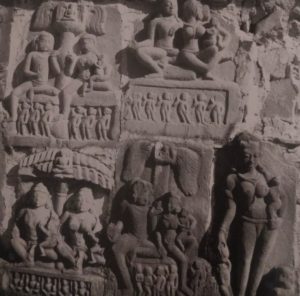

Illustration 151 (opposite) shows a motif which shall be designated as ‘resting queen”. The motif is well known from Hindu art, where the queen is always shown along with a child and is in some cases to be identified as Devaki-with-Krishna. In Jaina art, we find only very few specimens, and the child is shown nowhere. The motif has been identified by some as ‘mother of the Jina’.

No doubt, the mother of the Jina is often shown in Jaina miniatures from Western India (1100-1500), but the paintings do not help us to identify the sculptural motif which thus remains unexplained. In our photo, the left leg of the queen is bent and the right leg is placed upon it. The female figure to the left, much smaller than the queen, seems to massage the right foot of the queen, but it is not clear what exactly she is doing

A second female attendant figure is shown behind the queen’s head. In the back-wall of the niche we notice an unusual ensemble of motifs. A Jina image with lion throne and fly-whisk bearers is flanked by two-plus-two figures, probably all worshippers and including at least one emaciated ascetic (extreme left).

Further up we notice the remaining elements of the Jina image garland-bearing couple drum triple parasol with Ashoka tree drum garland-bearing couple. There is a marked contrast between the main group, which forms a harmonious whole, and the disconnected figures in the rear,

Illustration 152 shows a niche with two Jaina deities, which adjoins the queen’s niche to the right We see Kubera to the left and Ambika to the right Both deities are well known from Brahmanical iconography, Kubera being in Hinduism the Lord of Riches and Ambika being preceded by the of Hinduism, Some motifs in the composition are identical with or related to motifs surrounding the Jina (tree etc.), others are peculiar to Kubera and Ambika respectively. We mention only the latter.

Kubera carries a money-bag, now mutilated, in his left hand, while his right hand, which is gone, probably held a citron (up to the end of this paragraph, ‘left’ and ‘right’ are left and right as seen from the figure). An overturned jar with coins pouring forth from its mouth, is shown below Kubera’s left knee. The goddess Ambika keeps a child on her left knee, while a second. apparently elder child is standing to her right.

The goddess is sitting on a lion (its head is seen below her right knee), and her feet are placed on a lotus which rests on the lion’s back. Not all, but most of these elements belong to the standard iconography of the two deities A banana plant separates the two figures- and indicates that they are not directly connected, but are to be understood as attendant deities of the Jina who is in this case not a part of the composition.

In the early period (up to 950), Kubera and Ambika are often shown in the lower register of the Jina images to the left and to the right (see ill.155) Besides, Ambika and (occasionally) Kubera appear in Jaina art also as inde- pendent deities. Strange to say, neither Kubera nor Am bika occupy very prominent places in Jaina literature.

Gods and goddesses of every description surface in most phases of Jainism, but they are outside the soteri- ological plane, that is outside Jainism proper. They cannot help man to reach salvation.

soteri- ological plane, that is outside Jainism proper. They cannot help man to reach salvation.

Jaina images at Deogarh

We have now to turn to Deogarh. The Jaina temples of Deogarh boast of a great number of images, virtually the greatest concentration of Jaina images in the whole of India. Apart from the basic difference between “early- medieval’ and ‘medieval, we notice various shadings of style, including rather pronounced differences in the physiognomy of the different Jina figures. In addition to the Jina images we find numerous images of Jaina

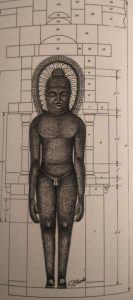

The great Shantinatha (height of the figure 3.73 m) in Temple No. 12 at Deogarh: organisation of the image.

The great Shantinatha. (Photograph by RAYMOND BURNIER) divinities, and there are also images of Jai- na monks. Miniatures figures of various di- vinities embellish the numerous pillars found in the temple compound. The great number of images is not the result of any concentrated scheme, but due to donations made over the centuries by pious Jainas, some rich and some without adequate means.

The great Shantinatha. (Photograph by RAYMOND BURNIER) divinities, and there are also images of Jai- na monks. Miniatures figures of various di- vinities embellish the numerous pillars found in the temple compound. The great number of images is not the result of any concentrated scheme, but due to donations made over the centuries by pious Jainas, some rich and some without adequate means.

This also explains the fact that some of the images show little artistic merit. Below we will mainly describe three first rate Jina images, belonging to Temples Nos. 12, 15, and 21 respectively. The first two images demonstrate the art of the early- medieval period, while the third belongs to the medieval period.

The first image is the great Shantinatha in Temple No. 12. Built before 862, this temple consists of a quadrangular structure which is crowned by a tall shikhara (tower). The quadrangular structure com- prises the sanctum and a circumambulatory passage.

Some time before 1350, a large pillared hall was built in front of the temple, and at a still later date (we do not know when) a ‘portico was prefixed to the pillared hall. (See ill.158, 159, and 162 for Temple No. 12 and its extensions, and ill. 153 and 154 for the Shantinatha image.)

Temple No. 12 has but few Jina figures on its outer walls. Contrary to Hindu temples, where the figures on the outer walls leave no doubt as to the Hindu character of the building, Jaina temples have a “neutral’ exterior. There may be wall figures of every provenance, but they are rarely clearly Hindu and rarely clearly Jaina. Jina figures in particular are inconspicuous or missing altogether.

As a consequence, the Jaina character of a monument may be recognizable, but it is never obtrusive – this was the price to be paid for the easily granted permission to erect Jaina temples under Hindu rulers. Moreover, there were no restrictions as far as the interior is concerned. In fact, the circumabulatory passage of Temple No.12 is jammed with colossal Jina images, and the sanctum (sanctum plus vestibule) houses, besides the great Shantinatha image, four standing images of the Jaina goddess Ambika.

If we allot the elements which surround the great Shantinatha to three vertical zones, we can ‘read’ the upper portion without difficulty. The VERTICAL ZONE TO THE LEFT has, from top to bottom, a male garland-bearer, a rosette, two leaves (- Ashoka tree), an elephant with small figures, a garland- bearing couple, four figures standing for ‘planets’ (numbers one to four), and the capital of a pillar.

The CENTRAL VERTICAL ZONE has from top to bottom, a drummer (hardly visible in our photography, two pannel roof, a vegetable composition, a single parasol roof, another vegetable composition, and the great hilo. The VERTICAL ZONE TO THE RIGHT is identical with the zone to the len, but the planets are numbers five to nine, the remaining members of a standard series of nine astral dreinities.

The miracle group is thus clearly represented with the fly-whisk bearers appear- ing further down in their appropriate fields (marked as in ill 153) The set of eight miracles has been amplified by a few additional motifs (runette etc), the result being a composition of considerable complexity.

There is a marked emphasis on the inward’ movement of the accessory figures (hovering geni, elephants fly-whisk bearers), creating the impression that gods and men flock together to worship the Jina The identy of the Jina (Shantinatha) is not indicated on the anage and follows only from a pillar inscription outside the temple in order to appreciate the impression conveyed to the visitor of the sanctum, one has to consider the size of the Jina composition (5 20 metres) and the semi-darkness of the room with its bare windowless walls. The facial expression of Shantinatha is stemn and reserved.

Impressive so the great figure is some visitors will prefer the style of the two flanking fy-whisk bearers and of the four Ambikas a faint echo of the Gupta age- to the severe expression of the Jina

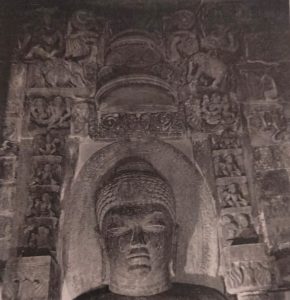

The Jina image of ill 155 is housed in the narrow sanctum of Temple No.15 (nee ill.158 and 162) The composition combines general aesthetic perfection with a convincing rendering of the theme of meditation The Indian art-historian KRISHNA DEVA observes:

“The main image of this temple, a masterpiece of early medieval art, represents a seated figure of Jina radiating spiritual bliss and effulgence and recalling in its sensitive modelling and serene expression the famous Gupta image of Buddha from Sarnath” In our description we concentrate on the image shown in the illustration but we ignore the superimposed register, which is not visible in our illustration.

This unconventional element repeats basically the motifs (standard motifs) of the top area as seen in ill. 155 (garland-bearers etc.) The portrayed lina has no cognizance, and, contrary to the Shantinatha of Temple No.12, exter- nal clues are likewise missing. One wonders what a temple with an unidentified main-idol was called by the worshippers.

The motif of the lion-throne is amplified by the addition of a cushion and two blankets Well-carved figures of Ambika and Kubera are seen to the left and to the right of the throne A Jina triad en miniature appears above each of the two attendant deities. Whereas the two previous Jina images were to some extent construed in an additive manner, we see in this case an integrated whole where each part contributes to the general effect of the composition.

This is best demonstrated by the motifs above the head of the Jina (parasol roofs etc.) which are arranged so as to form a self-contained ensemble. The carving of the composition is delicate, and some decorated surfaces such as the halo with its flower design must be viewed up close to be properly appreciated. Unfortunately, this image is among the pieces which have been altered in the course of the more recent operations.

A cognizance (an antelope in this case) has been incised into the lower blanket, and the Jina figure (including the halo) bas been darkened so as to make it stand out more clearly against the pale backslab. Since the medieval period we notice in Northern India the tendency of providing the lina figures more or less regulary with cognizances, but the incision of cognizances in existing

(anonymous) images has never been practised in the past Temple No 15 has merely a flat roof, but is a solid and well-planned building. By contrast, the small Temple No.21 (see ill.162), which homes our next image (ill.156), is one of those simple Jaina buildings (found at Deogarh and elsewhere) which were only constructed as shelters for Jina images and which cannot claim any artistic merit.

An inscription on the foot-band’ below the lion-throne tells us that a certain monk (or scholar) Gumanandin caused the image of Chandraprabha to be set up. Chandraprabha’s symbol, the crescent, is shown in the middle of the tracery course which appears below the “foot-band The trend to attribute separate identity to all the different Jinas is now fully

An inscription on the foot-band’ below the lion-throne tells us that a certain monk (or scholar) Gumanandin caused the image of Chandraprabha to be set up. Chandraprabha’s symbol, the crescent, is shown in the middle of the tracery course which appears below the “foot-band The trend to attribute separate identity to all the different Jinas is now fully

Unnamed Jina in Deogarh Temple No. 15-“a masterpiece of early medieval art” (Photograph courtesy American Institute of Indian Studies, Ramnagar)

Unnamed Jina in Deogarh Temple No. 15-“a masterpiece of early medieval art” (Photograph courtesy American Institute of Indian Studies, Ramnagar)

156 (right). The Jina Chandraprabha in Deogarh Temple No.21. “Now the image is but a ruin of what it was…”

developed, the vehicles of identification being in the first place inscriptions and cognizances (ymbols). Moreover, Kubera and Ambika, frequent attendant deities between e: 650-950, are now replaced by other divinities. The basic idea is to provide the 24 different Jinas with 24 +24 different attendant deities, a commendable theoretical scheme which represented the new trend, but was rarely legendary background, the elephants on which the fly-whisk bearers stand are a purely decorative if ever translated by the artists into practice.

In contrast to the elephants at the top which have some addition which enriches the new scheme. Stylistically, the Chandraprabha in No.21 is comparatively close to the image in Temple No. 15. However, medieval images clearly differ from early-medieval ones, even in those cases where the latter already seem to show the way to the new period. We notice

the case of the Chandraprabha unage deep undercutting where the projecting portions create an of depth which as in contrast with the comparative flatness of the earlier compositions. We abo notice an upward movement, a new lightness, in contrast to the earlier images where the figures are, in whole firmly planted on the ground. Of course, the shyness of the old fly-whisk bearers is and the figures seem to stare into the viewer’s face.

The aesthetic sentiment has changed. can be added that many model sculptures at Deogarh are dated and can even be used to date pieces at other places. The Chandraprabha image in preserved only through our photograph. In 1957 the image was still intact, although slight damage had occurred here and there, but “Now the image is but a rule of what it was the main figure and a number of subsidiary figures have lost their heads- The set-robbers, who ransacked only the medieval images, had brought havoc to one of the most expisite Jos images of that period The images shown in ill.

(four nutelary couples and one Ambika compare ill.149) demonstrate at a glance to what extent the Deogarh images differ both in their subject matter and in their aesthetic value. We see five tolerably preserved images of average quality which are fixed to the Great Wall.

(four nutelary couples and one Ambika compare ill.149) demonstrate at a glance to what extent the Deogarh images differ both in their subject matter and in their aesthetic value. We see five tolerably preserved images of average quality which are fixed to the Great Wall.

This wall (ill. 159) surrounds an incomplete square, including Temples Nos 12 and 15, which has this become the central area of the Juita compound. The images and fragments which are fixed with cement to this wall form an omnium gatherum of Jaina sculptures, including, of course, three or four very old pieces. One wonders where these sculptures had originally been arranged.

The image occupying the lower left of ill 157 cone of the four tutelary couples) is medieval and excels in “linear discipline, while the other four images of this illustration are early-medieval and recall a more gracious tradition. However, the five images are not very original from the point of view of style and Konography

The tutelary couple of Jains art as we can study it in ill 157 is always seated below a tree. A child is sy either on the lap of the female figure alone, or on the lap of both, the female and the male Detail of the Great Wall at Dengarh a small section of the sculp tural remains. GENTER HEWL) The Jaina temples of Deogarh before restoration and modernization. Photograph of the Archaeological Survey of India (1918) figure.

A frieze with a series of figures appears below the couple. This iconographic type is not mentioned anywhere in Jaina literature and has been imported into Indian art from Western Asia in the early centuries of the Christian era. At Deogarh the Jaina goddess Ambika is always shown under a mango tree, either standing or seated.

In ill. 157, the goddess is standing, as are the four Ambikas in the sanctum of Temple No. 12. The missing upper portion of the slab contained the mango tree.

There are quite a few images, tuny fragmentary, but almost all of good quality, which have not been fixed to the Great Wall, but lie in the open air, or in such places as the pillared hall before Temple No. 12. Finally, we have to mention a collection of small-sized and unimpressive Jina images housed in a shelter in the said pillared hall. This room has been created by the construction of plain walls between the four central pillars of the hall (see ill.162)

Jaina temples at Deogarh

We will conclude the discussion of Deogarh with a look at the central area of the Jains compound till 158, 159, and 162) Illustration 158 (above), one of the invaluable and rarely published old photo- graphs of the Archaeological Survey of India, shows primarily the complex of Temple No.12 shikhara temple, pillared hall (vertical arrow), and portico (diagonal arrow), all in axial alignment and

Deogarh 1994: The ‘portico of Temple No. 12 and the central area of the Jaina compound. (Photo by KURT TEEZE)

Deogarh 1994: The ‘portico of Temple No. 12 and the central area of the Jaina compound. (Photo by KURT TEEZE)

viewed from WNW. The other temples are Nos.7 (horizontal arrow). 14, 13 (13 behind 14, only the root visible), 15, 16, 23 (23-upper diagonal arrow), and 24 (lower diagonal arrow). The site is shown here after jungle clearing but before the execution of preservation measures.

The Great Wall as it exists today passes between No.7 and the portico of No. 12 (wall section running from north to south) and again between Nos. 15 and 16 (section running from east to west). The photograph was taken in 1917/18 during DRSAINI’s campaign and must be consulted in combination with a still earlier plan which was drafted in 1887/88 and where we have marked in our reproduction (ill.162) the position of the Great Wall (four arrows).

The photograph also shows how the comparative monotony of the Jaina group was relieved in Rajput times by the construction of numerous pavilions. Pavilions crown most of the flat-roofed temples, including Nos. 15 and 16. In the foreground we notice No.7, a pavilion which stands on the ground and forms an independent architectural unit.

Illustration 159 (1994) shows above all the portico of No. 12, which is here seen from SSW. This portico was assembled at an unknown date from re-used parts. The two front pillars are medieval and display on all sides exquisite carvings. Of the two pillars in the rear (both early-medieval), the one to the right bears an inscription which says that it (the pillar) was erected in 862 near the temple of Shantinatha (No.12).

We thus know that No. 12 was built before 862, and we also know that its main idol represents the Jina Shantinatha. In the photograph, we recognize the pillared hall before Temple No. 12 (from SW), Temple No.14 (also from SW), and above the Great Wall the roof of Temple No. 19 with its pavilion. Due to the modem roof which was built after the nineteen-fifties and which rests on its inner side on plain pillars, the visible side of the Great Wall lies in deep shadow.

The Department of Tourism has developed plans “to provide boating facilities in the Betwa River” and (as  we also read in the Hindustan Times of 20-3-94) “to revive the traditional facade of the Jain temples through restoration work.” Such statements are easily misunderstood. Deogarh has always been open to visitors, both Jainas and non-Jainas. Construction of roads and other measurements have changed the atmosphere of the locality to some extent, but not materially.

we also read in the Hindustan Times of 20-3-94) “to revive the traditional facade of the Jain temples through restoration work.” Such statements are easily misunderstood. Deogarh has always been open to visitors, both Jainas and non-Jainas. Construction of roads and other measurements have changed the atmosphere of the locality to some extent, but not materially.

Alterations in the archaeological substance will mainly be noticed by the specialists. Basically, Deogarh is still what it was, and those who see the place will be impressed by the splendour of its monuments and by the grandeur of primitive nature. “Deogarh is more than the sum of its published monuments.” To approach it by way of the River Berwa, then to follow the bridlepath that leads up the steep cliff past ancient rock-cut sculptures and on through secluded woodland this would be an ideal prelude to seeing the “virtually greatest concentration of Jaina images in the whole of (see pages 104 and 110).

“Deogarh is more than the sum of its published monuments.” To approach it by way of the River Berwa, then to follow the bridlepath that leads up the steep cliff past ancient rock-cut sculptures and on through secluded woodland this would be an ideal prelude to seeing the “virtually greatest concentration of Jaina images in the whole of (see pages 104 and 110).

P.C. MUKHERJI’S plan of the Jaina temples of Deogarh (1887/88). The drawing is not always accurate.

P.C. MUKHERJI’S plan of the Jaina temples of Deogarh (1887/88). The drawing is not always accurate.

but it gives a good idea of the site as it existed in the eighteen-eighties.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1. Bibliography

ANONYMUS (MB GARDE) The History & Monuments of Gwalior Fort. Published by the Department of Archaeology, Government of Madhya Bharat, Gwalior. No year- We have quoted from pp.2 and 25-26( late Jinas).

BANERJEE, NR. New Light on the Gupta Temples at Deogarh, in Journal of the Asiatic Society 5. 1963, pp.37-49-Vishnu Temple (‘Gupta Temple’) and Varaha Temple. BRUHN, K. The Jina-Images of Deogarh Leiden 1969.- Quotation from p.171 (the Chandraprabha image of our ill.153).

The Grammar of Jina Iconography I. in: Berliner Indologische Studien 8. 1995, pp. 229-83. CUNNINGHAM, A., Archaeological Survey of India, Vol.II. Simla 1871.-See pp. 330-96, for Gwalior GARDE, M.B., Archaeology in Gwalior, Gwalior 1934.

GHOSH, A., (ed.) Jaina Art and Architecture. Vols.I-III. New Delhi 1974-75. Refer to pp. 175-79 of Vol. 1 (KRISHNA DEVA) for a condensed survey of the Jaina temples at Deogarh and for a plan of the temple area (p. 176). Quotation from pp. 178-79(-> the image of our ill. 8).

GLASENAPP, H. VON, Jainism An Indian Religion of Salvation. Translated from the the original German by SHRIDHAR B. SHROTRI. Delhi 1998.

IMPERIAL GAZETTEER. The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Oxford 1908. Quotation from p.246 of vol. XI(Colonel Baptiste, – Jaina worshippers).

JOSHI, N.P.. “Two Days with the Scholar at Deogarh”, in: D. HANDA/A AGRAWAL (eds.) Ratna-Chandrika,

New Delhi 1989. See PP 167-74.

MEISTER, M.W.DHARY, MA. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture North India. Period of Early Maturity (e: 700-900), Text, Plates. Delhi 1991. Quotation from p. 48 t Gyaraspur).

MISRA, B.D., Forts and Fortresses of Gwalior and its Hinterland. New Delhi 1993, MUKHERJL PC Report on the Antiquities in the District of Lalitpur, N-W Provinces, India. Vols.I-IL 1899, SAHNI, DR., Annual Progress Report of the Superintendent, Hindu and Buddhist Monuments, Northern.

Circle, for the year ending 31st March 1918, pp. 7-25 VATS, M.S., The Gupta Temple at Deogarh. Delhi 1952. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India No.70.- Quotation regarding the- scenery of Deogarh taken from p. 1 (and selected by M.S.VATS from p.10 of the Jhansi District Gazetteer).

VIENNOT, O.. “The Mahishasuramardini from Siddhi(sic)-ki-guphu at Deogarh”, in: Journal of the Indian Society of Oriental Art. New Series Vol. IV/1971-72, pp. 66-77. WILLIAMS. J.G.. The Art of Gupta India. Princeton 1982

II. Acknowledgments and copyrights

Illustrations 149-152: sculptures on the Fort-rock, Gwalior. I have to thank once more GUNTER HEIL (Berlin) who directed my attention to little-known Gwalior sculptures and made the relevant negatives available to me. Refer in connection with our 149-150 also to BRUHN 1995, ill.

12-14.-153: see BRUHN 1969, ill. 394, -154: zee BRUHN 1969, ill8 (Photograph: RAYMOND BURNIER), -155: see MEISTER/DHAKY 1991, Pl.58.-156; see BRUHN 1969, ill. 211. 157: by GÜNTER HEIL-158: photograph in the Agra Office of the Archaeological Survey of India, 2205. 1917/18.-162: from PC. MUKHERJI 1899, pl. 13.-159, 160, 161: by KURT TITZE.

III. Frame of reference

In spite of a few references to changes in subsequent years, we have described in BRUHN 1969 the situation in 1954-57. This applies to our treatment of 319 Jaina images (mainly Jina images) as well as to other details (condition of the temples etc.). In subsequent publications, like the present one, we have still made the 1954-57 situation our basis and ignored later changes. We also plan to publish further Deogarh photographs (temples etc.) in order to record as far as possible the situation during or even before the time of our studies.

See page 5 for the Jinas and their cognizances.