Ranakpur

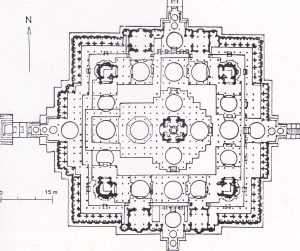

The grandest of the Jaina temples built after 1300 is the Adinatha Vihara (vihara = temple) at Ranakpur. It covers an area of 3720 square metres and its twenty-nine halls are supported by 420 pillars, none of which are alike. Building began in 1389, and took fifty years to complete.

The grandest of the Jaina temples built after 1300 is the Adinatha Vihara (vihara = temple) at Ranakpur. It covers an area of 3720 square metres and its twenty-nine halls are supported by 420 pillars, none of which are alike. Building began in 1389, and took fifty years to complete.

It was the fortunate constellation of four outstanding personalities to which we owe this marvel of a temple. First there was the Shvetambara Acharya Somasundara Suri, a great religious leader of his time.

personalities to which we owe this marvel of a temple. First there was the Shvetambara Acharya Somasundara Suri, a great religious leader of his time.

Close to him stood a young layman by the name Dharana Shah who was much devoted to the acharya and on his way of becoming minister to Rana (-king) Kumbha, being the third in the said constellation. Rana Kumbha, though not a Jaina by religion,  looked favourably on Dharana Shah’s plan for erecting a temple equal to the one he was shown in a dream.

looked favourably on Dharana Shah’s plan for erecting a temple equal to the one he was shown in a dream.

Eventually he, King Kumbha, was to give him the land needed to build the temple. Fourthly there was Depaka (or Depa), an unconventional architect whose imagination matched the visionary dream of Dharana Shah. The latter, by the way, took the vow of lifelong celibacy at the age of thirty-two, but being a minister to the king and committed to financing his ambitious project, he never became a monk.

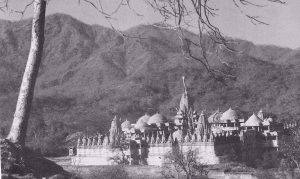

Ranakpur Adinatha Temple. Situated in the Aravalli Hills on the eastern bank of a small river, eighty-nine kilometres from Udaipur. There is a tourist bungalow close to the temple.

Ranakpur Adinatha l’emple. View into one of the twenty-nine halls carried by carved pillars.

Plan of the Ranakpur Temple also known as Dharna Vihara (after Cousens) Likened to lotuses, the 29 halls can be compared to a cluster of this Opo much adored Asian plant. The consecration ceremony was celebrated by Acharya Somasundara Suri in 1441.

With her eyes fixed on the Jina in the sanctum, a Shvetambara nun softly recites a prayer of devotion. The Ranakpur Vihara is more than an architectural feat. But it needs one’s presence at an evening puja to get a glimpse of the religious aura that arises in this majestic shrine whenever that is about every evening-pilgrims gather in the pillared hall before the sanctum in order to pay homage to the seated Jina by offering adoration, singing hymns and by finally waving lighted ghee wicks in front of the statue which for them represents the perfect teacher and paramatma (“supreme soul”).

With her eyes fixed on the Jina in the sanctum, a Shvetambara nun softly recites a prayer of devotion. The Ranakpur Vihara is more than an architectural feat. But it needs one’s presence at an evening puja to get a glimpse of the religious aura that arises in this majestic shrine whenever that is about every evening-pilgrims gather in the pillared hall before the sanctum in order to pay homage to the seated Jina by offering adoration, singing hymns and by finally waving lighted ghee wicks in front of the statue which for them represents the perfect teacher and paramatma (“supreme soul”).

It is during this final act of worship that the inlaid eyes of the Tirthankara image they being a Shvetambara peculiarity and regarded by many Westerners as an oddity- emit rays of light that be- stow an appearance of life upon the face of the idol. At this stage the foreign guest will no longer be a mere onlooker but a welcome and wholeheartedly accepted participant in this moving rite.

Scated Parshvanatha, main altar- piece in the Ranakpur Parshvanatha Temple.

Strange to say, this grandiose temple, though it remained largely spared by fanatic iconoclasts thanks to an order by the great Mughal emperor Akbar at the request of a Jaina monk, was left to decay in later centuries. There came a time when pilgrims no longer dared to visit the temple for fear of wild animals and dacoits. At long last, after the administration of the temple was handed over to the Anandji Kalyanji Trust, a thorough restoration, taking eleven years to complete. began in 1933.

Foreign visitors to Ranakpur should note that the so-called ‘high priest’ of the temple is not a Jaina but a Vishnuite Hindu. This extraordinary arrangement applies to almost all Shvetambara shrines. Regarding Ranak- pur, the ‘priestly’ position is passed on from father to son, and this since fourteen gen- erations within the same family.

At the beginning of the performance of a play at the court of princes in India in the Middle Ages, the reader used to step out upon the bare boards and relate to his audience what he saw about him in his mind’s eye; his words then called to life corresponding images in their consciousness, and they served as decorations and wings.

The public was credited with so much imagination that it was capable of retaining in its mind imaginary surroundings as an ever-present frame of reality. – Udaipur seems to me to have been created by similar evocations, to be real in the same sense. Udaipur seems so improbable in its beauty that I stand in the midst of it, look at it and enjoy it as if in a dream.

Count Hermann Keyserling (1880-1946)

Indian Travel Diary of a Philosopher, Bombay, 1969.